ARKHAM ACADEMY

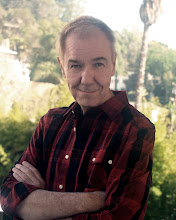

Mini-Series Proposal by Gerry Conway

We know Bruce Wayne had loving parents until both were murdered when he was a young boy. We know he spent his late adolescence and early manhood traveling the world, learning the skills that would enable him to become the world’s greatest crime fighter.

What we don’t know, really, is what happened to Bruce in the years between his childhood and late adolescence.

Now we will.

As Batman investigates a murder with links to the “lost years” of his mid-adolescence, we’ll learn what happened to young Bruce Wayne during his first year at the “special school” for the troubled youth of Gotham’s wealthiest — and, some of them, most corrupt — citizens.

We’ll learn about Bruce Wayne’s first encounter with the “velvet prison school,” Arkham Academy.

A child traumatized as Bruce Wayne was by witnessing the murder of his parents can react in a number of ways — by withdrawing into himself, by acting out violently and aggressively, by losing his ability to create and maintain functional relationships.

Bruce, between the death of his parents and the year he turned 14, reacted in all of these ways. First, he withdrew into the safe cocoon of Wayne Manor, into the loving care of Alfred Pennysworth and, at times, Doctor Leslie Thompkins. He shunned contact with the outer world. He attended school only sporadically, preferring to study at home, away from others. Under the legal guardianship of the Wayne Foundation board of directors, his increasing alienation from the world around him suffered from “benign neglect” — until an incident on his 14th birthday sent his life in an entirely new direction.

Attending the dedication of a new children’s wing named in his father’s memory, a sullen and too-tightly-wound Bruce overhears one of the younger patients make an adolescent wisecrack about Doctor Thomas Wayne: “How good a doctor could he’ve been if he’s dead?” Years of pent-up and submerged rage explode. Bruce attacks the wheelchair-bound boy, shoves him over, and in tears, runs from the hospital. Stumbling blindly into the busy street, he causes a several-car pile-up. While no one is seriously injured, there are obvious legal and financial repercussions.

Determined to put Bruce on the “right track” (and to soften the Foundation’s financial liability for Bruce’s actions), the Wayne Foundation Board — as his legal guardians — ships Bruce off to a special school for troubled youths. This school is Arkham Academy.

Founded by an offshoot of one of Gotham City’s most prominent families, Arkham Academy — on the surface — is an idyllic retreat. Situated on a small island upstate on the Gotham River, Arkham Academy can be reached only by a single small bridge from the mainland. The bridge is gated and guarded by the school’s uniformed security patrol for “the students’ protection.”

In reality, Arkham Asylum is a velvet prison.

The co-ed student body at Arkham is composed of sons and daughters of the wealthiest families on the East Coast, along with “scholarship” kids added to the mix to promote ethnic and social diversity. (A requirement forced upon the school’s board of directors by its original early 20th-Century charter.)

Most of these “troubled kids” are victims of ordinary adolescent angst and parental neglect; trophy children of wealthy couples too self-involved to raise their offspring themselves, they’ve been shipped off to a variety of boarding schools over the years, and for one reason or another, they’ve ended up here. Some students are exceptionally bright, a few are emotionally damaged ordisturbed, and a handful are out-and-out sociopaths.

But the student body is only part of the troublesome mix that makes Arkham Academy a volatile environment: The faculty is equally… diverse.

Among the handful of caring and idealistic teachers are those who are not what or who they appear to be. Several teachers conceal dark pasts.

At least one member of the faculty is a secret murderer whose ghoulish appetites will put everyone at Arkham Academy in deadly danger.

Welcome to high school, Bruce.

Time to start growing up, fast.

Over a twelve-issue arc, the “Arkham Academy” mini-series will follow two story-lines: the present-day murder investigation by Batman with origins rooted in his first year at school on that remote island; and a parallel story, exploring that year as Bruce Wayne experienced it.

Along the way, Bruce will gradually develop relationships with the others students, and with the teachers. These relationships — first friendships, first romance, first conflicts with rivals and enemies, a first experience with an older mentor — will put Bruce on the path away from withdrawn, angry loner, and toward the more integrated (yet still damaged) man he’s destined to become.

When Bruce arrives at Arkham Academy, he has one goal: to get out, to escape, and to remain untouched and unconnected to others.

By the end of the twelve-issue arc, however, he’s made friends with fellow students and at least one of the teachers, developed a romantic relationship with a young woman, and learned what it means to be part of a larger social group.

He goes from potential sociopath to an integrated member of society — though still somewhat a loner, he recognizes that he’s not, ultimately, alone.

At the end of this first year, after solving a murder mystery and helping to save the lives of people who’ve become important to him, Bruce is given the opportunity to leave the Academy. He’s given the chance to fulfill the only goal that mattered to him when he arrived at the isolated island school.

To his own surprise, Bruce makes his first real, autonomous decision as a young adult.

He decides to stay.

“Arkham Academy” operates on several levels: as a Batman-driven super-hero murder mystery; as a Bruce Wayne-driven coming of age story; and as a (hopefully) fun teen soap opera with mystery adventure overtones.

Arkham Academy is a combination of Hogwarts and Smallville, with a touch of “Shutter Island” and “Lord of the Flies” tossed in for spice.

As such, it creates an opportunity both to expand the Batman/Bruce Wayne story, and, outside of comics, has potential for development in series television or film. (I can easily see “Arkham Academy” replacing “Smallville” on the CW schedule when the later show ends.)

But most important, it’s got the potential to be a damn good story.

You think?